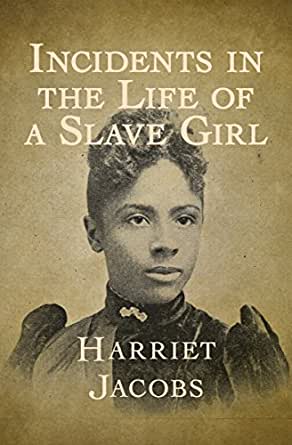

This book was written (and published in 1861) to inoculate northerners against southern sugar-coating of slavery. This passage exemplifies its purpose:

One day I saw a slave pass our gate, muttering, ‘It’s his own, and he can kill it if he will.’ My grandmother told me that woman’s history. Her mistress had that day seen her baby for the first time, and in the lineaments of its fair face she saw a likeness to her husband. She turned the bondwoman and her child out of doors, and forbade her ever to return. The slave went to her master, and told him what had happened. He promised to talk with her mistress, and make it all right. The next day she and her baby were sold to a Georgia trader.

Another time I saw a woman rush wildly by, pursued by two men. She was a slave, the wet nurse of her mistress’s children. For some trifling offense her mistress ordered her to be stripped and whipped. To escape the degradation and the torture, she rushed to the river, jumped in, and ended her wrongs in death.

Senator Brown, of Mississippi, could not be ignorant of such facts as these, for they are of frequent occurrence in every Southern State. Yet he stood up in the Congress of the United States, and declared that slavery was ‘a great moral, social, and political blessing; a blessing to the master, and a blessing to the slave!’ (pp. 135-136)

So attuned to hypocrisy, Jacobs takes special aim at the church, as in the following scene:

I well remember one occasion when I attended a Methodist class meeting. I went with a burdened spirit, and happened to sit next to a poor, bereaved mother, whose heart was still heavier than mine. The class leader was the town constable – a man who bought and sold slaves, who whipped his brethren and sisters of the church at the public whipping post, in jail or out of jail. He was ready to perform the Christian office any where for fifty cents. This white-faced, black-hearted brother came near us, and said to the stricken woman, ‘Sister, can’t you tell us how the Lord deals with your soul? Do you love him as you did formerly?’

She rose to her feet, and said, in piteous tones, ‘My Lord and Master, help me! My load is more than I can bear. God has hid himself from me, and I am left in darkness and misery.’ Then, striking her breast, she continued, ‘I can’t tell you what is in here! They’ve got all my children. Last week they took the last one. God only knows where they’ve sold her. They let me have her sixteen years, and then – O! O! Prey for her brothers and sisters! I’ve got nothing to live for now. God make my time short!’

She sat down, quivering in every limb. I saw that constable class leader become crimson in the face with suppressed laughter, while he held up his handkerchief, that those who were weeping for the poor woman’s calamity might not see his merriment. Then, with assumed gravity, he said to the bereaved mother, ‘Sister, pray to the Lord that every dispensation of his divine will may be sanctified to the good of your poor needy soul!’ (pp. 78-79)

“No wonder,” Jacobs writes, “the slaves sing, –

‘Ole Satan’s church is here below;

Up to God’s free church I hope to go.’ (p. 84)

The founding principles of our republic fall under the charge of hypocrisy too; yet despite their authorship by slave-mongers, they inspire. When Jacobs slips away from her tormentors, she resolves that, “come what would, there should be no turning back. ‘Give me liberty, or give me death,’ was my motto.” (p. 111) If Patrick Henry hadn’t meant for his declaration to be echoed by everyone, then he shouldn’t have blared it.

Instrumental as she no doubt was in helping to crystalize public opinion against actual slavery, Jacobs would not join in the mounting mid-century chorus against “wage slavery,” or bourgeois society, that was first voiced experimentally by Thoreau (“It is hard to have a southern overseer; it is worse to have a northern one”), developed heroically by Gandhi (“Formerly, men worked in the open air only as much as they liked….Now…their condition is worse than that of beasts….They are enslaved by the temptation of money and of the luxuries that money can buy”), and finally reprised in satire by Orwell (“Freedom is slavery”). On a trip to England after her escape, she observes:

I had heard much about the oppression of the poor in Europe. The people I saw around me were, many of them, among the poorest poor. But when I visited them in their little thatched cottages, I felt that the condition of even the meanest and most ignorant among them was vastly superior to the condition of the most favored slaves in America. They labored hard; but they were not ordered out to toil while the stars were in the sky; and driven and slashed by an overseer, through heat and cold, till the stars shone out again. Their homes were very humble; but they were protected by law. No insolent patrols could come, in the dead of night, and flog them at their pleasure. The father, when he closed his cottage door, felt safe with his family around him. No master or overseer could come and take from him his wife, or his daughter. They must separate to earn a living; but the parents knew where their children were going, and could communicate with them by letters….There was no law forbidding them to learn to read or write; and if they helped each other in spelling out the Bible, they were in no danger of thirty-nine lashes, as was the case with myself and poor, pious, old uncle Fred. I repeat that the most ignorant and the most destitute of these peasants was a thousand times better off than the most pampered American slave. (pp. 205-206)

This edition comes with a narrative by Harriet’s brother, John, which includes this pithy farewell note to his “master”:

Sir – I have left you, not to return; when I have got settled, I will give you further satisfaction. No longer yours, John S. Jacob. (p. 248)