The next scene foreshadows the meeting of the hero and heroine. The image is by Satomi Kamei.

Watching Nanjing fume from the sky or from the ground, neither Peng bird nor human would have noticed the elderly nun on a donkey cart making her way through the smog from Cock-Crow Temple on the north side of town to outside Treasure Gate, the southernmost portal of the city wall. Though missiles whizzed by her, she maintained her dignity, as did her cart driver, who seemed to have absorbed a bit of her gravitas. The nun was called One-Eyed Jingang, for partially blinding herself while studying the Diamond (Jingang) Sutra, and she was Cock-Crow Temple’s abbess. While unaccompanied women raised eyebrows if they ventured abroad on most days, the Spring Festival provided One-Eyed Jingang not only with the cover of smoke but also with an excuse to be out, for clergy were often called upon to offer prayers for the New Year. In fact, One-Eyed Jingang was expected at another place of worship, a monastery named the Temple at the Edge of Heaven, where a prayer meeting was planned for that morning. Before the chanting began, however, she wished to consult with the abbot on a matter of some delicacy.

Arriving at the Temple, One-Eyed Jingang alighted from the cart, paid its driver a little extra for the New Year, walked through the main gate, and ascended the stairway to the Mahayana Pavilion, where the abbot, whose dharma name was Baichi Shi’ai, or “Idiot in the Service of Love,” greeted her with ebullient good cheer. Fearless of gossip, he invited the nun into his office.

“Wisdom to you,” he saluted her, offering some tea. “Big Sister is a bit early. Have you come to help me choose today’s reading?”

“No, Big Brother,” the abbess returned, as she sat down on a stool. “I’m sure you’ve already found something appropriate. As it turns out, I’ve come to discuss something…inappropriate.”

She placed on Baichi Shi’ai’s desk the bulging sack she’d been carrying, which the abbot had assumed to be filled with boxed or string-bound folios of sutras. She untied the twine at its neck, just as somebody in the neighborhood set off another string of firecrackers like a drumroll.

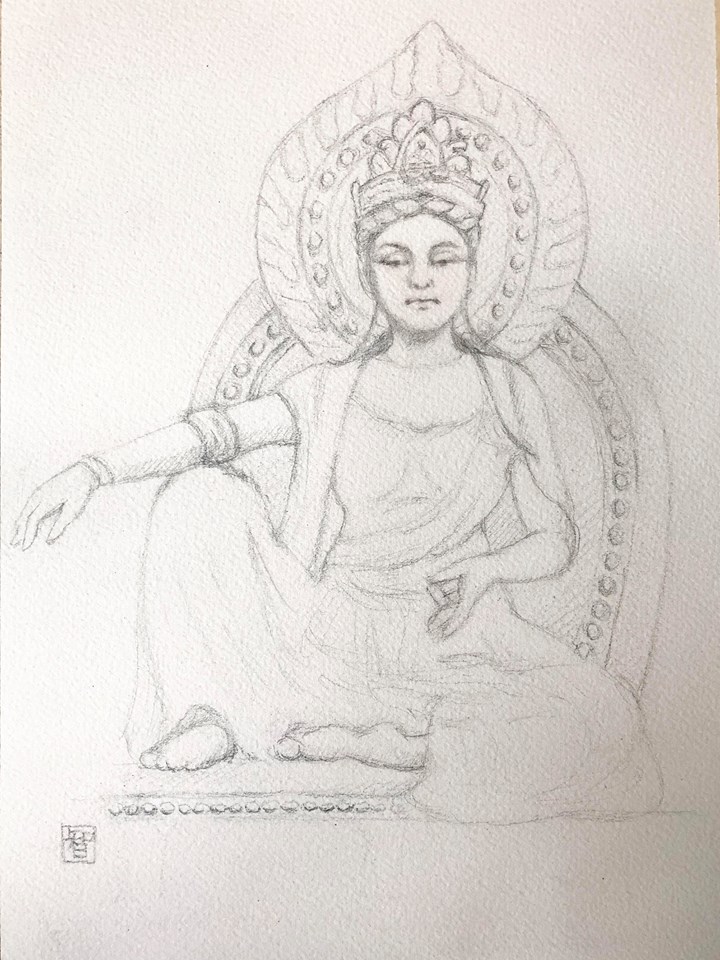

The sack fell away, revealing a statuette of the Guanyin Bodhisattva, sculpted from rosewood. The carving stood about a foot tall, but its subject did not stand, nor did she sit cross-legged in stolid meditation. Rather, she lolled in a sultry position with one leg arched upward at a right angle, her arm draped over her knee. Although she was Guanyin, the Goddess of Compassion, she posed in the style of Tara, Mother of Liberation; but whatever compassion or liberation she offered her worshippers, it was of a primal, physical sort. Her sexuality was total, not of parts. It sprang not from flaring hips or curvaceous breasts but from her unworldly air of assurance and utter lack of inhibition. Against all convention, this Guanyin held her eyes open, inviting her faithful to advance and be saved. A mandorla of fire radiated from her body, a manifestation of the power of her love.

Baichi Shi’ai knew better than to resist the goddess’s charms. Instead, he gave rein to his native enthusiasm. “Oooh! Hail, Guanyin Bodhisattva!” he crowed.

“Yes, she does rather demand devotion,” observed One-Eyed Jingang. “I’m surprised you haven’t fallen to your knees.”

“Whose hands crafted such a powerful image?” asked the abbot. “Or was it a bolt of lightning striking a grateful tree that did the work?”

“Actually, it was created by one of my novices, a brilliant girl. Always reading, trying her hand at something new. I noticed her chiseling away at a hunk of wood from that old column we had replaced and decided to give her a bit of rosewood to see what she could do with better material. This is the result.”

Baichi Shi’ai nodded, still absorbed in Guanyin’s smoldering expression. “Where will you display it?” he asked, after a while.

“Display it?” the abbess exclaimed. “Good brother! It’s hard enough to protect the reputation of my convent without having something like that on a pedestal. Why give the next scandalmonger a chance to start yapping about the ‘lewd nuns of Cock-Crow Temple’?”

Baichi Shi’ai rounded his mouth. “Oh? You think this Guanyin is lewd?”

“No, I do not, but a lewd man would, and I’m tired of hearing lewd men talk nonsense about decent nuns.” One-Eyed Jingang cleared her throat. “So I was hoping that you, Teacher, would take this Guanyin off my hands.”

“And keep her here?” the abbot giggled. “My monks would explode! Even if I hid her away, they would sniff her out like tom cats.”

“You have that little faith in your brothers?”

“I have that much faith in my brothers.”

One-Eyed Jingang slumped. “Yes, I suppose we face the same difficulty. Since our calling is to free people from desire, it’s bad policy to introduce an object of desire into either of our sanctuaries. So what should we do with it?”

Baichi Shi’ai grinned. “You talk as though she were a problem to be gotten rid of, but Guanyin Bodhisattva cannot be a problem. Yes, neither of our temples is the proper place for her, but remember: Guanyin embodies compassion for the world.” He raised both his arms, in an encompassing gesture. “Let’s put her out into the world, then, where her compassion can do its work. If some starry-eyed lad falls in love with her, so much the better. Everyone in the world needs to be receptive to compassion, after all.”

One-Eyed Jingang thought for a bit and then nodded. “Yes, Brother, you are right. We should allow this Guanyin to play her part. I will consign her to the marketplace, to await the first receptive soul that comes along.”

She put the Guanyin back in its sack and tied it closed.

“So what will be today’s reading?” she asked, but her host didn’t answer, and both devotees of dharma continued to stare at the enshrouded idol for a long time.