Having recently infiltrated the Mobile (Alabama) Writers Guild, I was asked to complete the following interview form. The result is somewhat arch; so I’ve decided to post it here.

Name: Harry Miller

Facebook/Twitter/Social Media:

yellowcraneintherain.blog

(I’m also on Facebook)

Anything published?

State versus Gentry in Late Ming Dynasty China, 1572-1644

State versus Gentry in Early Qing Dynasty China, 1644-1699

The Gongyang Commentary on the Spring and Autumn Annals (A Full Translation)

When did you start writing?

When did you first realize you wanted to be a writer?

Why did you start writing?, etc.

I began writing in middle school, because it was required of me by my teachers. The latter praised what I had written, and I accepted their praise, proud to be considered a good writer. Apparently, the quest for external validation has always been my chief motivation as a scribbler.

At any rate, with my pretentions thus encouraged, my literary endeavors soon went beyond class assignments. I kept a diary in the tenth grade and have occasionally revisited journal-writing since graduating from college, especially during discrete life experiences such as periods of overseas adventure, including a stint in Taiwan from 1988 to 1992. I also wrote many letters, in the last decade or so before letter-writing became obsolete.

Though I gave no thought to the process of choosing a profession before turning twenty six, I always wanted to be a writer of some kind, even if only as an amateur. I was particularly inspired by historians such as C.V. Wedgwood and Francis Parkman, and I dreamed of creating monumental works like theirs. In my late twenties, finding amateurism, too, to be a thing of the past and sensing that it was time to put up or shut up, as far as my dreams were concerned, I committed myself to the academic career path, reasoning that it would offer the most practical chance of realizing them. Putting my college major and post-graduate experience (and language ability) to use, I selected Chinese history as my area of expertise.

After twenty years of credentialing myself academically and establishing myself professionally, during which time I also started a family, I have accomplished my ambition by authoring three historical epics (listed above), which are very well thought of by the twenty or so people who have read them.

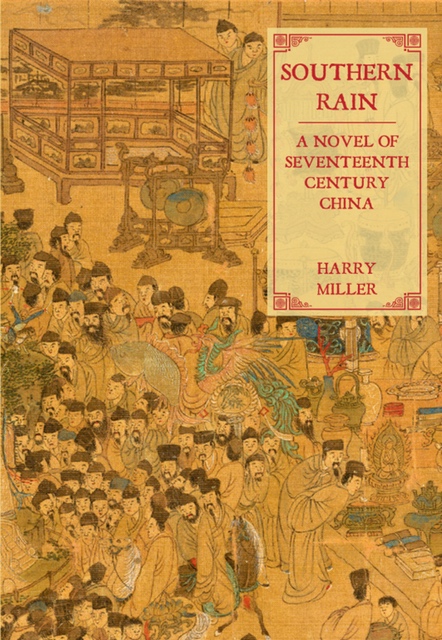

In search of a larger audience, I have turned to historical fiction. My first historical novel, Southern Rain, tells the story of an ordinary young man and an extraordinary young woman in seventeenth-century China, who struggle to get and stay together in the face of cultural and political obstacles. It explores the relationships between men and women and freedom and power, against the backdrop of dynastic upheaval. I have tried to make it not only historically realistic but also accessible and engaging to the general reader. The book has been accepted for publication by Earnshaw Books, and I’m quite happy that it’ll be out there soon – in paperback, no less!

Beyond Southern Rain, I’ve got a few more ideas in me. For example, I’d like to translate an account of a creepy family from seventeenth-century China into English and then transplant it to Renaissance Italy. There’re also several straight translations from Chinese and Japanese that I wish to undertake.

How long does it take you to write a book?

About two years.

What is your work schedule like when you’re writing?

I work in the mornings, on days when I am not teaching.

Do you ever experience writer’s block?

If something is giving me trouble, it may bother me for a day and a night, but the “bother” is usually just my mind solving the problem. In Southern Rain, for example, I didn’t want the heroine, Ouyang Daosheng, to have bound feet. After obsessing over the matter for a while (and consulting a few other historians), I determined that an upbringing in a nunnery would probably have spared her the agony.

How do books get published?

I don’t know how other authors’ books get published. Mine get published by the grace of God.

Where do you get your information or ideas for your books?

From Chinese history. The climatic episode of Southern Rain is a historical event from 1645, of which I learned while researching my second book.

Do you work with an outline, or just write?

I just write. The outline takes shape in my head.

When did you write your first book and how old were you?

State versus Gentry in the Late Ming came out in 2009. I was 43.

What do you like the most about writing?

Getting it right. It’s torture until then, euphoria afterward.

What do you like to do when you’re not writing?

Canoeing, reading, music, movies, and sleeping.

What does your family think of your writing?

My mom and brother seem to like Southern Rain.

What do your friends think of your writing?

My friends love my writing (letters, etc.), but none has read any of my books, no doubt because they are put off by the supposedly alien nature of the subject matter (China).

What has been the toughest criticism given to you as an author? What has been the best compliment?

The worst criticism a reader can give is that he doesn’t understand what I’ve written, which means that I’ve failed as a writer. The best compliment is “You’re a great writer.”

Is anything in your work based on real life experiences or purely all imagination?

Some of the settings in Southern Rain are based on places I’ve visited. The protagonist’s house in Nanjing, for example, is based on a place where I used to eat (which was someone’s house). I’ve traveled on the Grand Canal in China, which helped me visualize my characters’ travels by the same method in my book.

As for the characters of Southern Rain, the male protagonist, Ouyang Nanyu, I suppose may be based on me; and Ouyang Daosheng may be a composite of every woman I’ve known – for all I know.

Do you plan on making a career out of writing?

Since I obtained tenure by publishing, I’m happy to say that I already have.

What is your favorite type of book to read?

I like to read histories, novels, historical novels, and books on contemporary issues (such as law), in turn.

What was the last book you read?

Pride and Prejudice

What is currently on your to read list?

The Pendragon Legend, by Antal Szerb

What do you listen to when you write?

Nothing.

What is your favorite music?

The Beatles (though they’ve been going in and out of style, with me)

What is your favorite quote?

“As I hung upon the rail I occasionally turned to watch the captain and the mates who were motioning and swearing in all directions until no one knew his own business.”

— Stephen Crane, “Dan Emmonds”

What is your favorite candy?

A Japanese white chocolate wafer called Shiroi Koibito – “The White Lover”

What would I find in your refrigerator right now?

Acai juice

Have you ever played patty cake?

I play it all the time, with the gentleman who mows my lawn.

Have you ever gone out in public with your shirt on backwards, or your slippers on, and when realizing it, just said screw it?

Shirt on backwards and slippers on is overdressed for me.

Do you go out of your way to kill bugs? Are there any that make you screech and hide?

I don’t kill bugs, except, occasionally, for cockroaches. In Taiwan, where cockroaches are the size of lobsters, the only way to kill them is by pounding them with your fist, upon detection. If you run to get a newspaper or something, he’ll be gone by the time you return. I got pretty good at it.

Is there anything unique about you that you’d like for us to know?

I am the only person in the world with no unique qualities.

Is there anything that you would like to say to your readers and fans?

Where are you?